The Lighthouse of Alexandria (Pharos)

The Eastern Harbour viewed from Trianon window. This site had, for several years, been the busiest in the ancient world. It was the quay where building materials had unloaded during the construction of the 138-metre high Lighthouse of Alexandria, completed in 12 years starting around 280 BC. The Pharos was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, radiating rays of light and of Alexandria’s superior episteme to the whole world for 1,600 years. It also projected a mixture of real events and myths, together making up Alexandria’s story: Cleopatra’s defenders of the city re-angling the giant mirrors atop the lighthouse to focus the strong sunrays, burning the Roman ships; or the light dying when the keeper vanished (he has originally been the only surviving mariner from a shipwreck whose sailors were blinded by the Pharos’ light).

Muhammed Ali Pasha

The statue of Muhammad Ali Pasha on his horse in Alexandria’s Place des Consuls was erected during the reign of Ismail Pasha. According to Alexandrian folklore, the pasha’s statue has, ever since, been a protector of the city he had resurrected over six decades earlier. When the British bombed Alexandria for two days in July 1882 – reducing the area to rubble and damaging the British, Greek and French consulates on the square – only the pasha on his horse remained standing high above the ruins. Muhammad Ali Pasha’s protective magic also prevailed during the Second World War when the Luftwaffe subjected Alexandria to the worst air raid that an Allied city outside Britain was to sustain, as Rommel’s panzers approached. None of the bombs fell on the square, and the one that dropped nearby failed to explode. The campaign by Colonel Nasser (who spent his childhood in Alexandria) to tear down the history and memories of Alexandrie royale stopped at the square that Muhammad Ali Pasha protects. The officers didn’t dare remove his statue, as they had done with those commemorating the rest of his dynasty. Superstitiously, the street signs announcing its new name ‘Midan-el-Tahrir’ were carefully placed away from where the pasha’s gaze fell.

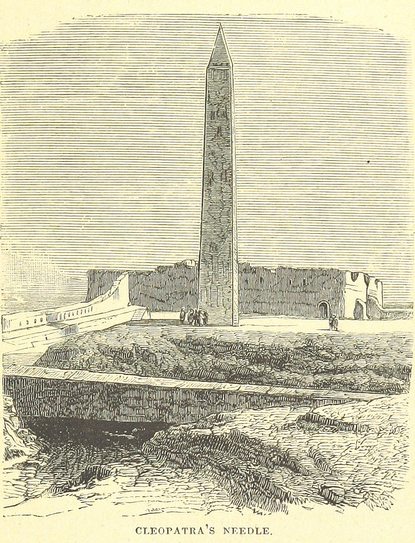

Cleopatra Needle and Alexandria's folklore

One of Alexandria legends grants extraordinary powers to Alexandria’s last queen, the beloved Cleopatra, who is credited with saving her obelisk twice from sinking in stormy seas on the voyage taking it to its final destination in England. British engineers came up with the idea of a 29-metre-long by 5-metre-wide floating cylinder – built by engineers the Dixon brothers and named ‘Cleopatra’ – to contain the excavated 21-metre, 224-tonne obelisk, which was given as gift to Britain in 1820 by Muhammed Ali. This cylinder was towed by a steamer called the Olga manned by Captain Henry Carter and crew in September 1877. A Force-8 gale in the Bay of Biscay led to the temporary loss of ‘Cleopatra’. Six sailors from the Olga who volunteered to rescue the Cleopatra crew and their skipper, Captain Booth, perished when their boat capsized. Finally, after several attempts, Booth and his sailors were lifted on to the Olga. On 14 October, Captain Carter had to cut the towing ropes following a mutiny by his sailors because of ‘bad spirits’ that they believed were on the floating cylinder and had caused the storm. The voyage’s own ‘albatross’, so the folk tale goes, was the armour and bones of a Roman soldier found buried with the obelisk, which a sailor had stolen and put in the cylinder along with the needle. After it was widely believed that the ‘Cleopatra’ had sunk, she was – miraculously – found once the storm ended by the Fitzmaurice, bound for Valencia, and was towed into Ferrol, Spain. Negotiations regarding the salvage rights and cost took another three months, but finally the Alexandrian queen’s supernatural powers rescued her famous needle, and the ‘Cleopatra’ was towed – by another steamer, the Carter-captained Anglia – into London’s East India Docks in January 1878. In September that year, it was moved to its current location by the Thames.